Why Docker Networking Matters

Containers don’t automatically know about each other. If you run three isolated services:

docker run node1docker run node2docker run nginxThey are like strangers living on the same street.

- They share the same system

- But have no idea the others exist

- They can’t talk to each other

To solve this, Docker provides user-defined bridge networks, which allow communication inside Docker without exposing containers to the outside world.

Part 1: Writing a Minimal Node HTTP Server

Each backend server will respond with HTML page that identifies itself.

Create a folder docker-lb-example

mkdir docker-lb-example

cd docker-lb-example

touch server.jsinside it create server.js

const http = require("http");

const os = require("os");

const PORT = process.env.PORT || 3000;

const SERVER_NAME = process.env.SERVER_NAME || os.hostname();

const server = http.createServer((req, res) => {

const hostname = os.hostname();

const time = new Date().toISOString();

const html = `

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Hello from ${SERVER_NAME}</title>

<style>

body { font-family: Arial, sans-serif; padding: 20px; }

h1 { color: #333; }

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello from ${SERVER_NAME}</h1>

<p><strong>Hostname:</strong> ${hostname}</p>

<p><strong>Current Time:</strong> ${time}</p>

</body>

</html>

`;

res.writeHead(200, { "Content-Type": "text/html" });

res.end(html);

});

server.listen(PORT, () => {

console.log(`Server ${SERVER_NAME} listening on port ${PORT}`);

});

We use:

SERVER_NAMEas an environment variableos.hostname()as a fallback- Plain HTTP — no frameworks to distract from networking

Dockerizing the Node App

Create a Dockerfile:

FROM node:18-alpine

WORKDIR /app

COPY server.js ./

EXPOSE 3000

CMD ["node", "server.js"]

Build the image:

docker build -t node-server .We now have a reusable container image.

Part 2: Creating a Private Docker Network

This network will contain all three containers.

docker network create mynetWhy is this important?

- Containers on

mynetcan talk to each other by name - Docker automatically resolves container names → IPs

- Network is isolated from everything else

Production infrastructure relies heavily on this pattern.

Part 3: Starting Two Node Backend Servers

We’ll run two containers from the same image, each with a different identity.

docker run -d \

--name node1 \

--network mynet \

-e SERVER_NAME="container-1" \

node-server

docker run -d \

--name node2 \

--network mynet \

-e SERVER_NAME="container-2" \

node-server

There is no -p flag. These containers are not exposed to your host. They can only communicate inside the Docker network. This is how microservices stay private.

Part 4: Verify Connectivity Inside the Network

Spin up a temporary container:

docker run -it --network mynet alpine shInstall curl:

apk add curlHit each container by name:

curl node1:3000

curl node2:3000You should see HTML from each. This is Docker DNS working behind the scenes. There is no central database. Docker resolves names automatically.

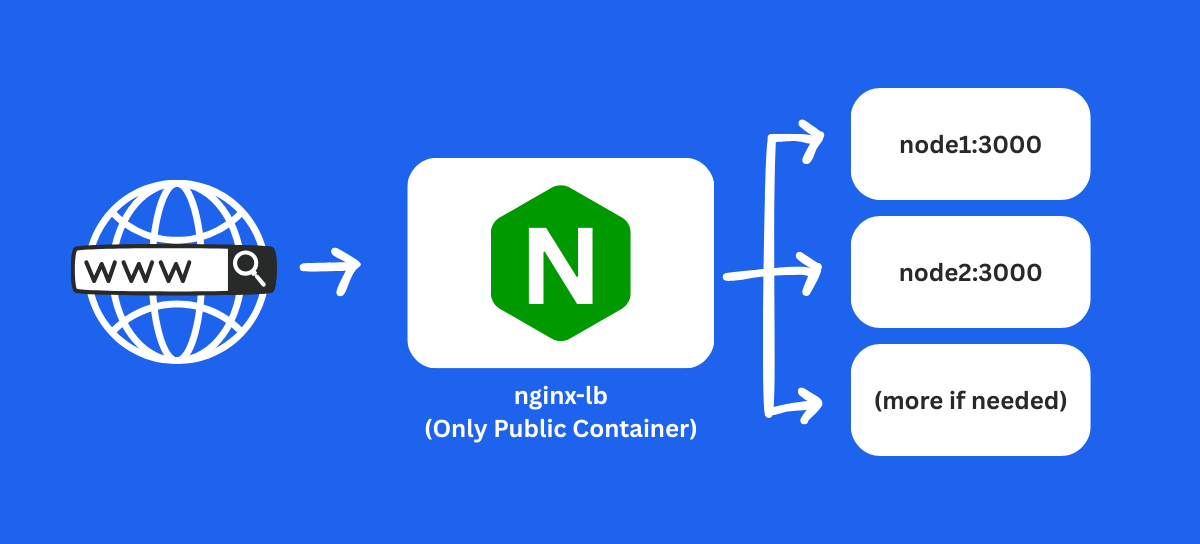

Part 5: Introducing nginx as a Load Balancer

Modern backend systems rarely rely on a single service. APIs, workers, and web servers often live in separate containers that communicate over private networks.

A load balancer distributes incoming requests across multiple servers.

We’ll use nginx because:

- It is lightweight

- It is production-proven

- It supports reverse proxying and balancing natively

Create a file:

events {}

http {

upstream appservers {

server node1:3000;

server node2:3000;

}

server {

listen 80;

location / {

proxy_pass http://appservers;

}

}

}

Explanation:

upstreamdefines a backend pool- nginx picks a server using round robin (default policy)

- Container names (

node1,node2) act as hostnames

No IP addresses needed. You can restart containers without breaking the config.

Part 6: Running the Load Balancer Container

Launch nginx attached to the same Docker network:

docker run -d \

--name nginx-lb \

--network mynet \

-p 8080:80 \

-v $PWD/nginx.conf:/etc/nginx/nginx.conf:ro \

nginx:alpineWe expose only the load balancer to the host.

Traffic flow becomes: Browser → nginx-lb → node1 or node2

Part 7: Test It

From your host:

curl http://localhost:8080Run it a few times and you can see it serves content from both containers. This demonstrates round-robin balancing.

What You Just Built

A real-world production pattern:

- Public entry (nginx)

- Private microservices (node1, node2)

- Internal communication only

Why This Matters

1. Security

- Only one public “door”.

- Nodes are private.

2. Scalability

- Want 10 servers? Just run more backend containers.

3. Fault tolerance

- If node1 fails: nginx automatically routes to node2

4. Portable architecture

Same design works on:

- AWS ECS

- Kubernetes

- Docker Swarm

- Bare-metal servers

Key Takeaways

- Containers do not communicate by default — they are isolated environments unless you explicitly connect them through networks.

- User-defined Docker networks enable private container communication, letting services talk to each other securely without exposing ports.

- Docker DNS resolves container names automatically, so services can reference each other using names like

node1ornode2instead of IP addresses. - Backend services should stay private — we never exposed

node1ornode2to the host, only the load balancer. - nginx acts as a gateway, receiving public requests and forwarding them to backend containers using reverse-proxy rules.

- Round-robin balancing happens automatically in nginx, allowing requests to be distributed evenly without custom logic.

- Scaling is trivial — you can launch more containers on the same network, and nginx will route traffic to them.

- This architecture mirrors real-world infrastructure used in Kubernetes, cloud environments, and microservices systems.